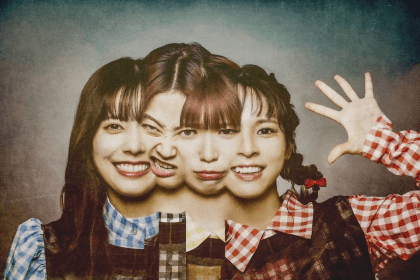

A few weeks back a curious feature popped up on the Hyper Japan website. It was a puff piece designed to draw attention to the fact that Dempagumi.inc are to perform at the summer event, which is big news considering that Dempagumi are currently one of the most high profile J-Pop acts in Japan at the moment.

A few weeks back a curious feature popped up on the Hyper Japan website. It was a puff piece designed to draw attention to the fact that Dempagumi.inc are to perform at the summer event, which is big news considering that Dempagumi are currently one of the most high profile J-Pop acts in Japan at the moment.

However, the feature ran with an odd line that addressed the “idol-sceptics” who might be concerned that Dempagumi were another AKB48. Considering that Hyper Japan is a Japanese cultural event whose purpose is to promote Japanese pop culture, this was a bizarre comment to make. How did we arrive at a point at which a Japanese pop culture event felt duty-bound to apologise for one of its acts?

To understand this you have to look at much of the commentary and debate that gets churned out by various channels, including some Japanese news outlets and a raft of click-bait blogs.

Amongst some of these outlets, there does appear to be a consistent mantra being beamed out which is “IDOL MUSIC IS BAD AND YOU SHOULD FEEL BAD”. This is usually dressed up with a fig leaf around the issues and problems inherent in the Japanese music industry. Or, alternatively, exploiting any element of scandal associated with an artist.

There’s plenty of room to invite discussion on the issues within the Japanese music industry without either railroading musicians to endorse your point or indeed having to demonise artists or their fans. This is how debates are constructed after all. Also, many of the arguments are not necessarily without merit (we’ve addressed some of them in interviews with Japanese musicians here in the past). The problems start when there’s either a conflict of interest – or an attempt to exploit a situation in order to boost traffic. It’s very easy to mistake an op-ed piece as factual for instance.

What appears to be taking place is an attempt to invoke a guilt trip amongst fans of Japanese music. It’s a fait accompli that suggests our default position is as “idol sceptics”, therefore everyone should apologise for either promoting them (Hyper Japan) or indeed for being fans to begin with.

Back in 2004, a BBC documentary series called The Power of Nightmares, aired. The series was subtitled ‘The Rise of the Politics of Fear’ and explored the way that fear can be politicised. In other words, with the right approach you can broadcast a message that hits particular buttons that induce unease and fear. It’s a method that tabloid newspapers use to whip up fear of immigration for instance.

It’s ironic then that much of this discussion taking place in the depths of the interwebs is an attempt to employ fear and sow the seeds of distrust – because of their own fear of idol groups. It’s rock outfits or J-Pop apparently with no middle ground. You’re not allowed to enjoy both your Joy Division albums and your KPP albums, so choose only one.

Music is, of course, a very broad tapestry so attempting these comparisons often comes across as a clumsy, self-serving screed. Many bands simply cannot make the leap between keeping a low profile indie aesthetic to a commercially successful outfit. Sometimes it’s purely unwillingness on behalf of the band to make that jump. There are certainly a select number of bands and artists, for instance, that shun interviews or publicity.

This doesn’t denigrate those bands in any way, but illustrates that artists operate at many different gears within the wide world of music. Why would anyone want to distil that down into one homogenous whole?

What has also become increasingly clear is that the people promoting this message are generally unwilling to enter into debate on the topic. Because to do so would suggest that there are other sides in the issue, when their battle is to put forward a partisan position that is unassailable. So a few familiar tactics are wheeled out to derail attempts at starting a dialogue. This can range from belittling or screaming at people on Twitter through to sourcing an unfavoured band on any detractor’s social network profile and using that as a pretext to shut down the debate.

Tackling the Japanese music industry from a western perspective also presents its own problems. There are cultural differences that require a gear change when constructing a position. But any mention of ‘cultural differences’ results in the antagonists throwing a tantrum about how cultural differences are not relevant, which is essentially an example of western voices aggressively employing their own cultural standards (or what we would call ignorant prejudice).

Does this mean that cultural differences automatically deflate any argument? No. But they can colour certain topics and certain debates. Failure to acknowledge this – and indeed offering a knee jerk response – just makes you come across as another ranty Howard Beale character.

Another point of attack is the fans themselves, who are often described as caricatures of otaku stuck in their parent’s basement (and often with the suggestion that their interest is more prurient than musical). The methods of CD sales is also brought up in which many idol music fans may buy hundreds of copies of a typical single to acquire voting slips to support their favourite members.

This, say the detractors, artificially boosts sales. But that fault doesn’t lie with the fans or indeed the idol groups, it’s an issue that lies within the structure of the Japanese music charts – a rather sizeable target if you’re aiming correctly.

Secondly, regardless of whatever fantasy world these critics may carry around in their heads, a decent tune is going to get more mileage – both commercially and in appreciation – than some wailing dirge presented by the latest indie outfit whose sole claim to fame is topping the bill on Thursday’s band night at the Japanese equivalent of the Dog & Duck. Nothing against fans of wailing dirges, but it’s two wholly incompatible ends of the Japanese music spectrum.

It seems strange to think that we, as western commentators, can claim to occupy the higher moral ground in this debate. Then again, we enjoy a western music scene that is completely devoid of scandal and controversy. After all, it’s an industry that has brought us such unassailable paradigms from Led Zeppelin to Michael Jackson. We have a history of democratic management teams looking after our artists. Our charts reveal only the brightest and best talents and are definitely not gamed in any conceivable way. Go us.

Which brings us rather neatly back to where we started. If the UK’s largest Japanese pop culture event feels it’s necessary to apologise for the acts that it’s engaging, then it suggests that perhaps we – as J-Pop fans – need to make more of an effort in challenging the constant mantra being broadcast from some quarters with a more positive endorsement of J-Pop from our end.